The humble fruit fly is helping scientists who are working to find a cure for brain tumours. The tiny insect, often viewed as a household nuisance, has helped researchers to better understand mechanisms which turn a healthy cell into a tumour cell.

The work is taking place at the Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at the University of Plymouth and is helping us get a better understanding of glioma tumours, which include low and high-grade types with glioblastoma (GBM) being the most commonly-diagnosed high-grade brain tumour in adults.

Dr Claudia Barros (pictured above) and her team have uncovered “readying” processes which occur just prior to brain tumour onset that could be vital for tumour growth – more work is needed to understand these very early changes but slowing or preventing tumour growth is vital in improving quality of life and survival rates for patients.

Dr Barros said: “The research contributes to understanding of how brain tumours could form and has opened up avenues of research to find new potential drug targets towards novel therapies for patients with glioma tumours.”

“Using the fruit fly Drosophila as a model, we have been able to identify and examine cells at the very initial stages of brain tumour formation inside the brain. These cells have most striking differences in their metabolic and protein balance landscape compared to normal cells.”

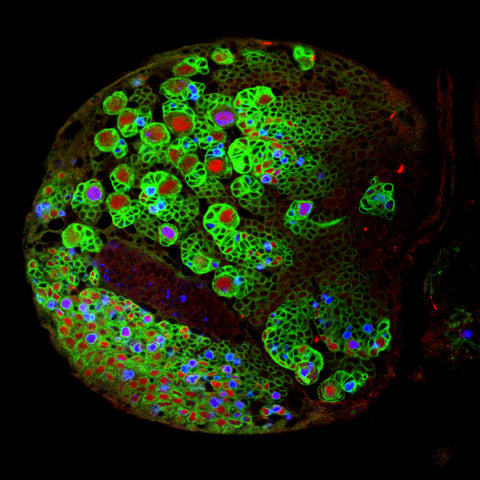

Fruit fly brain stem cells (credit: Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at the University of Plymouth)

Fruit fly brain stem cells (credit: Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at the University of Plymouth)

Using the data they uncovered, the research team identified a mechanism by which a protein known as HEATR1 – the overexpression of which is linked to poor prognosis in glioma – works with the major growth regulator known as MYC and is required to increase the production of ribosomes, which are essential cellular machinery for brain tumour growth.

Dr Karen Noble, our Director of Research, Policy and Innovation, said: “There is much work still to be done but these early findings are significant because, with more investigation, it could help us develop new treatments which will target tumour cells more effectively and so improve outcomes for patients.

The work has recently been published in the journal, EMBO Reports.

Related reading: